The Australian Government has unveiled a $19 million funding package to support the development of artificial intelligence technologies for healthcare, including a number of groundbreaking mental health initiatives.

The latest funding supports research and development in a variety of artificial intelligence technologies designed to help prevent, diagnose, and treat medical conditions and manage mental health.

Among the recipients for the R&D funding package include the University of Sydney, the University of NSW, St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research, and the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

As part of the funding pool, the University of Sydney will receive more than $3 million to support improvements in youth mental health care. The project will assess the use of artificial intelligence in guiding clinical decision-making and in managing the intervention and treatment of physiological conditions.

The University of New South Wales will receive up to $5 million for its AI project to optimise treatments for stress, anxiety, and depression.

Additionally, the Centre for Eye Research Australia will receive a portion of the funds to develop an AI tool to optimise the detection of eye disease.

St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research will utilise its funds to develop AI-backed breast cancer screening tools.

Technical details on the funded projects have yet to be outlined. The Government noted, however, that artificial intelligence would serve to better assist healthcare professionals in understanding the day-to-day patterns and needs of the people they cared for.

AI drives quality health care, but has limits

Federal Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, said AI was critical to the future of quality healthcare. Funds for this program have been drawn from the Government’s $20 billion Medical Research Future Fund.

Government grants from the Future Fund are designed to improve the efficiency of research, Hunt said, together with streamlining clinical decision-making and offering technology-led approaches to healthcare delivery.

The Australian Government included AI funding as part of its 2018-19 Budget, committing $29.9 million to projects including research funding, more PhD places, and educational programs in schools and at the undergraduate level.

In a recent report, the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Science, though noting some very stark deficits, said that AI could support better prediction, prevention, diagnosis, and management of diseases.

“AI technologies could revolutionise health technology and delivery – if developed and deployed responsibly,” it said, serving to reduce stressful workloads for clinicians.

However, it hazards to stress, “in health, things are not straightforward”.

“There are risks and challenges, of course, such as the validation of AI technologies, the potential malevolent use of AI, data security or manipulation, or misdiagnosis leading to suboptimal care,” the Academy said.

“[In] many cases the outcomes associated with using an AI in one context could be precisely the opposite in another.”

Such technologies may, in fact, increase stress levels for specialists, for instance, where their caseloads focused only on the most complex patients.

“Some uses of AI might deliver efficiencies that lower the costs of care, but others could increase costs due to the extra demands on resources and infrastructure,” the Academy said.

Moreover, more formalised ethical principles and guidelines were needed to protect patient data and maintain the high standards of healthcare and research.

The Department of Industry, Innovation, and Science and the CSIRO’s Data 61 have developed an overarching framework for the ethical use of AI across multiple sectors, including health.

The ethics framework was designed to monitor the design, development, and implementation of artificial intelligence systems, the Academy observed. While the framework was not mandatory, it nevertheless offers useful guidelines to ensure responsible use of AI in clinical settings.

Broader adoption of AI would require public confidence in the ethical bounds of these systems and tangible measures to ensure machine-generated problem-solving replicated more intuitive thinking by humans, the Academy noted.

Global trends in medical AI

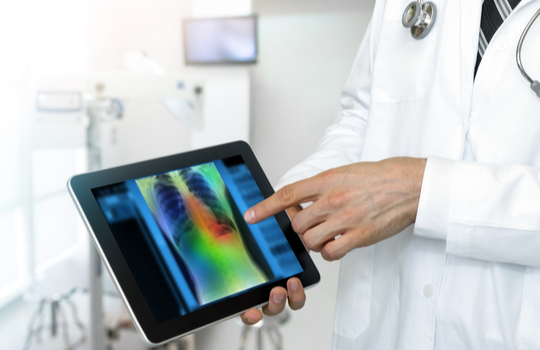

Among some notable trends in ‘clinical artificial intelligence’, researchers from Google Health, based in the US, recently programmed its AI to read mammography screenings in an effort to improve detection of potential malignancies and aid one-the-ground medical staff, a New York Times story revealed.

The team found that their AI model could predict breast cancer from scans with similar accuracy to expert human radiographers.

Further, the AI showed a reduction in the proportion of cases where cancer was incorrectly identified – with a 5.7 per cent reduction in false positives in the US tests alongside a 1.2 per cent reduction in the UK.

AI is also being trained to recognise patterns of disease or interpret tomography scans, backed by algorithms to detect lung cancers within CT scans or diagnose eye diseases in people with diabetes.

The proliferation of consumer wearables and other medical devices has also been combined with AI to detect early-stage heart disease, enabling doctors and other caregivers to better monitor potentially life-threatening episodes at earlier, more treatable stages.